Italians in the Delta: “Pioneers of Monroe”

By April Clark Honaker

The Italians in Monroe, Louisiana, are a small, tight-knit group of successful, family-oriented people who have established deep roots in the Delta while maintaining a connection to each other and to their home country, despite pressures to become mainstream Americans. Even though Italians were the largest immigrant population of turn of the 19th century Louisiana, they have remained understudied. Surprisingly, the Italians once comprised the biggest immigrant population in Louisiana, totaling 20,233 in 1910 (Cordasco and Bucchioni 40).

However, many Italian immigrants were quick to adapt and disappear in the melting pot of American life if doing so meant a chance at greater success. According to Joseph Logsdon, whose focus was Italians in south Louisiana, “[A]ssimilation had to come at the expense of Italian-American ethnicity. It was (and is) necessary to divest oneself of the outward signs of one’s Italian-ness in order to climb the vaunted ladder of ‘success’ in the American social system” (26).

Thus, at a glance, the Monroe Italians appear to be fully assimilated. Despite this fact, their inner Italian-ness remains very much intact. As a group, their origins and religion are similar to other Louisiana Italians, but they are pioneers whose own family stories and traditions truly bond them.

Striking Out on Their Own: Italian Settlement in Louisiana

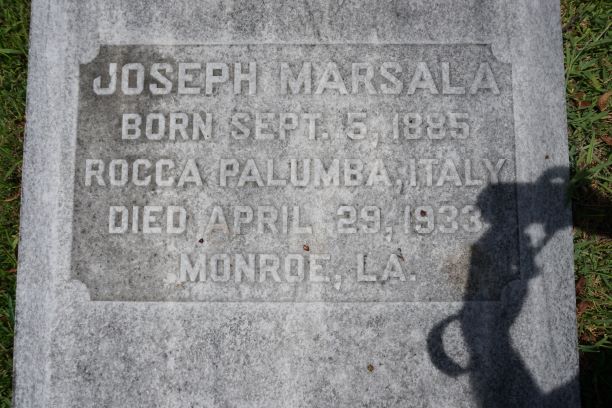

Most of Louisiana’s first-generation Italians were farmers who came from poor regions in southern Italy and Sicily in the late 19th and early 20th century, and they were looking for success. Industrious and motivated, many of them were able to turn the meager wages they earned working sugarcane and other crops into enough money to strike out on their own (Becnel) or to return to their home country (Boudreaux). Frequently, Italians who came through the Port of New Orleans worked hard on local farms, saved enough to buy land, and settled around Independence in Tangipahoa Parish where they could profit from the booming strawberry industry (Becnel). However, others travelled further north, many on the railroad. A few settled near rivers in towns such as Waterproof, Vidalia, and Lake Providence (Gregory), but many were drawn to urban areas across the Mississippi and Louisiana Delta, such as Monroe.

By 1928, Monroe had a population of just over 27,000, and according to the Monroe-West Monroe Chamber of Commerce at the time, “‘The eyes of the nation’s investors [were] turned toward Dixie where . . . a prosperous empire [was] rising'” (qtd. in Harvey 28). Many Italians who had managed to accumulate enough money to invest found opportunities in Monroe, Louisiana. Once settled, they often established businesses, including bars, bakeries, grocery stores, restaurants, and fruit stands. According to Tony Cascio and Anthony Bruscato, descendants of immigrants in Monroe, many of the Italians there owned rental houses in addition to starting small businesses. Delta Italians also took advantage of educational opportunities to ensure that future generations were able to climb further in socioeconomic status (Wilson).

According to Gregory, some Italian families in the Delta have since seen their offspring establish careers as doctors, lawyers, and scholars. Indeed, Tony and Marguerite Cascio confirm this trend. Tony Cascio said, “Most of the Italians here—they weren’t well-educated. Most of them didn’t go to college,” and Marguerite Cascio continued, “They were just working people, [but] I would say the third generations were your lawyers and your doctors. We have quite a few of them now.”

By 1928, Monroe had a population of just over 27,000, and according to the Monroe-West Monroe Chamber of Commerce at the time, “‘The eyes of the nation’s investors [were] turned toward Dixie where . . . a prosperous empire [was] rising'” (qtd. in Harvey 28). Many Italians who had managed to accumulate enough money to invest found opportunities in Monroe, Louisiana. Once settled, they often established businesses, including bars, bakeries, grocery stores, restaurants, and fruit stands.

According to Tony Cascio and Anthony Bruscato, descendants of immigrants in Monroe, many of the Italians there owned rental houses in addition to starting small businesses. Delta Italians also took advantage of educational opportunities to ensure that future generations were able to climb further in socioeconomic status (Wilson). According to Gregory, some Italian families in the Delta have since seen their offspring establish careers as doctors, lawyers, and scholars. Indeed, Tony and Marguerite Cascio confirm this trend. Tony Cascio said, “Most of the Italians here—they weren’t well-educated. Most of them didn’t go to college,” and Marguerite Cascio continued, “They were just working people, [but] I would say the third generations were your lawyers and your doctors. We have quite a few of them now.”

Grasping Opportunity: The Italian-American Dream

The dream of making a better life for themselves and their families drew many poor Sicilians to Louisiana. Anthony Bruscato, a third-generation immigrant and practicing lawyer in Monroe, has spent much time reflecting on what might have motivated these immigrants: “I think it was remarkable. I guess it was the time. It was occurring around the world—not only the Italians and predominantly the Sicilians, but people all over Europe—Eastern Europe, and Asia, and whatever—migrated to the United States. There was a lot of hardship, poverty, lack of opportunity, repressive governments, people looking for some room and for some opportunity to better themselves and provide a better opportunity to their children. That’s what had to have drove them to what they did because the migration to the United States was worldwide. “

Bruscato said news began to circulate through letters and care packages back and forth from Monroe to small towns in Sicily—Cefalu, Caccamo, Vicari, Salaparuta, and Corleone—that one could leave home and find family in Monroe. According to Marguerite Cascio, word of job opportunities also traveled back to Sicily: “The way I understood it, you had to have somebody more or less not sponsor you, but you had to know someone living here that would probably offer you a job. You almost had to have a job promised to be able to come in to the country.”

Still the people drawn by the American dream and the promise of support were disproportionately poor. Even Bruscato could not imagine why a family of firm middle class standing would want to relocate, but for those with little prospects, the decision was easy:

If you’re poverty-stricken, no job, no opportunity, can’t find the funds to buy clothes or food for your family, and you make and do, and your diet is horrible, and you hear that there’s a place over there, another place in the world—there’s jobs, there’s opportunity, you can achieve things you want to do in life, I guess the attraction would attract anybody. . . . I guess that’s what happened.

Though many Italian immigrants came into Louisiana with nothing, they quickly got busy pursuing the American dream and often found the work easier if they joined forces with other Italians.

Building Little Italy: A Network of Pioneers

Once settled in Monroe, the Italians stuck together, building and supporting one another’s businesses, creating “a little network” according to Bruscato. Along with businesses, they built homes and established Italian social clubs, such as the Columbus Social Club and the Progressive Men’s Club. Bruscato believes it was his mother’s uncle Antonio Messina who built the first Columbus Social Club at the corner of DeSiard and Sixth around 1906. His description of the Monroe club illustrates the importance of the site in maintaining Italian folk traditions such as rituals and music:

And every area where all of these immigrants, and particularly Sicilians, they all stuck to each other when they got where they were going. Here in Monroe, of course Christopher Columbus is a national hero of Italy, and most Italians wherever they populated in the United States would start a club called the Columbus Social Club. And we had one in Monroe, Louisiana. While on the rooftop [of the club]—if you talk to the old timers the immigrants—they would have their socials up there, they would have their weddings, their receptions, their birthdays or gatherings. My grandfather on my father’s side played the accordion and he was part of the entertainment. Somebody else would play this instrument, so it was a close knit—where the Italians would get together and enjoy each other’s fellowship and friendship. Most of them were members of that club.

According to Bruscato, these clubs, especially the Columbus Social Club, were a favorite site for weddings, receptions, birthdays, and other celebrations. They served as a point of connection for the Monroe Italians, as well as a place for them to celebrate their Italian-ness.

Both Bruscato and Tony Cascio also reported that the overall Italian presence in Monroe was much greater than most realize. They were involved in the community at every level. While small grocery stores were a common livelihood for Italians, Bruscato said, “Not all Italian immigrants opened grocery stores.” Italians did many things to provide for their families. Vincent Anzalone, a second-generation Italian, said his family initially had barber shops.

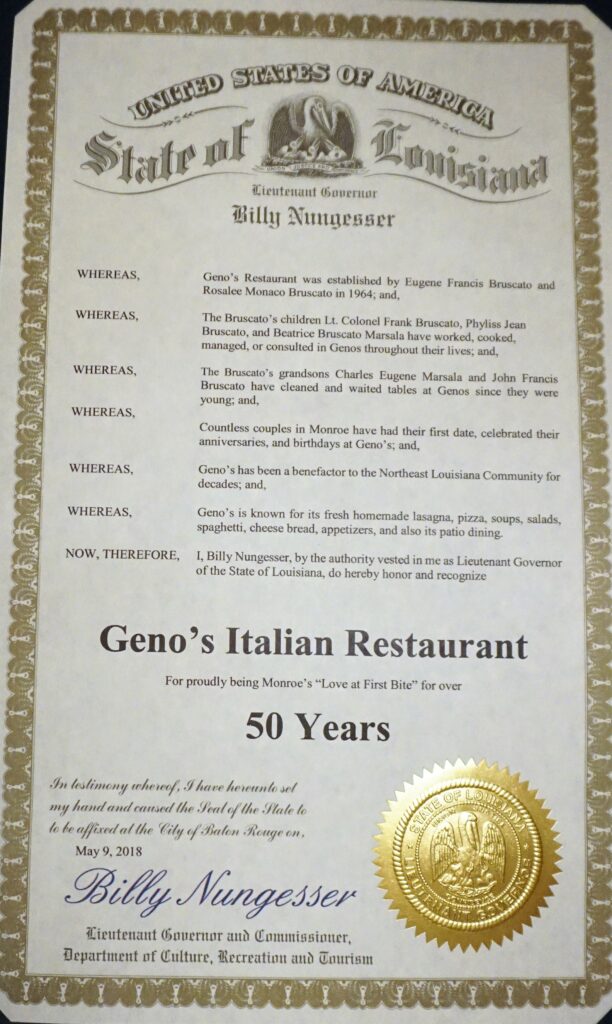

Then in 1940 he and his brother opened a hardware and furniture store: Star Hardware. Cascio said his father started “just about any type of business you can name: a grocery, a barbeque business, and we had a little dry cleaning plant. All this was on Oak Street . . . where we was born. He had a little Italian restaurant too. That’s the way we all took off from there, you know.” In addition to owning small businesses, Italians worked in city government, ran buses and trolleys, and practiced trades including carpentry, tile setting, general labor, and plumbing. Many passed on their trades to their children.

According to Cascio much of downtown Monroe was populated by the Italians up until Mayor Howard expropriated the land needed to build the Civic Center. Cascio said,

Where the fountain is [in front of the Civic Center] that was my daddy’s property. In fact when they . . . cleared all that out, that was “Little Italy.” From Seventh Street back to the railroad, where the Civic Center is, all that property was “Little Italy” . . . . Well, you can call it “Little Italy” because they had so many in there. . . . You know you had about 500 houses that they destroyed when they built the Civic Center.

Cascio was not sure what year the land was taken, but the Civic Center was built in 1965, and the changes did little to slow progress for the Italians, especially the Cascios. Cascio explained,

So when the city took our property, me and my brother-in-law had a little old bar on the end down there, so they bought it from us, and we just borrowed, we all, me and my brothers, borrowed money from the rest of the family. That’s how we went into the restaurant business, and, of course, we had it all together. We had eight or ten restaurants in Monroe.

Bruscato also recalls how his father who continued in the family grocery business came back from World War II “and moved to Louisville and Riverside streets where he converted a large building into a place to live and some commercial outlets.” According to Bruscato, after a few years, his father became restless and wanted to try something else:

[H]e had this wanderlust attitude that the world was bigger than Monroe, L. He sold [our] house, and I remember him counting the money on the kitchen table, what he received in the proceeds of that sale, and he bought . . . a brand new Studebaker, a land cruiser, and he bought a late ’30s truck, ton and a half truck. Loaded all the furniture and hired a driver and with the three boys and my mother and father, headed west. It took us three weeks to get to California because there were places along the way he might have wanted to stop and live, but he kept going. I guess if it wasn’t for the Pacific Ocean we’d still be going west. Well, anyway we stayed out in California from my age eight till age sixteen in southern California and L.A. County and then came back to Monroe in 1956.

Though the Bruscato groceries no longer exist in Monroe, their legacy remains. Tony Cascio remembers them: “Yeah, Bruscato’s folks had a place . . . right next door there [to Star Furniture] . . . they had a big grocery store with fresh seafood back then. Hell, that’s before the war so we’re going way back, and that’s how we started in the restaurant business . . . fresh seafood. That was our secret.” In many ways, it seems the Italians were a very connected group in Monroe, often telling stories about each other.

In fact, Bruscato told about the Varino family’s grocery business and the impact it had on the community, especially smaller grocers. His story describes a process in which credit trickled down in the hardest times:

There was a family here in Monroe, their last name was Varino, and they were from a small town near Caccamo on the coast called Termini Imersi. And he still has relatives there. When he came over, Frank Varino and his wife, they had a large family. He was in the Wholesale Grocery business. It was located on Trenton Street, the old section of West Monroe. Well, all of his children worked in that wholesale grocery business, and they would be salesmen making rounds with these grocery stores that these Italians were running, and that was where they would get their credit to get in to business—to stay in business. All this transpired in the teens and the twenties and thirties, during the depression. So it was extremely important they got credit, these people who had these grocery stores.

The customers that would come into these grocery stores would also get credit. To a large measure most of them were African Americans where the businesses were located. And they would get credit. So it’s interesting how the credit line was extended from the wholesaler down to the ultimate purchaser, particularly during hard times when people didn’t have any money to buy food but they needed food and they found credit. So there was a great deal of affinity among grocery store operators and the people who traded with them, because they could always go down there and get something to eat. Every one of them had a little box with what is the credit balance that you owe.

Such stories suggest the loyalty the Italians had to one another and their concern for the wellbeing of the community as whole, not just for their personal advancement.

I love reading your site.

I love reading your site.

I noticed one of your pages have a 404 error.

Comments are closed.