The Quest to erect Historic Markers to the Sicilian Migration to New Orleans on Contributions to Safety, Culture, and Economic Development started in 2017.

Sicilians began arriving in New Orleans in the 1820s on the lemon boats and worked in French Market and the docks of New Orleans. By 1860, approximately 1,200 Sicilians lived in New Orleans. Italy did not become a country until 1861.

Starting in the 1880s, over 60,000 Sicilians were brought into Louisiana via New Orleans to work on plantations. Within three years, many had oved to New Orleans and opened grocery stores, which they lived above. Estimates are over 50% of grocery stores in Louisiana were owned by Sicilians by 1910.

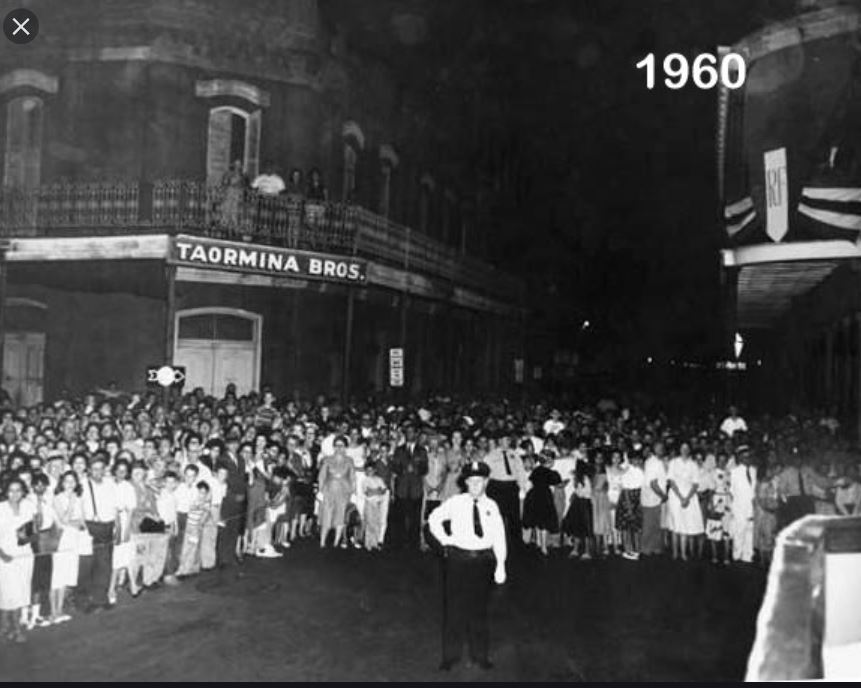

In 1897, the Dingley Tariff was passed on imported pasta. As a result eleven pasta factories opened in the French Quarter of New Orleans. The Taromina Pasta Factory was across the street from the proposed marker site.

The marker application process started in February of 2019 by attending a class by the state of Louisiana.

In May of 2019 two submissions are made to the State of Louisiana Dept. of Tourism for Historic Markers.

In June of 2019 after approval by the Dept of Tourism, the submissions are sent to LSU History Dept.

In July 2019 after approval by the LSU History Dept., the submissions are sent to a State Commission for Approval.

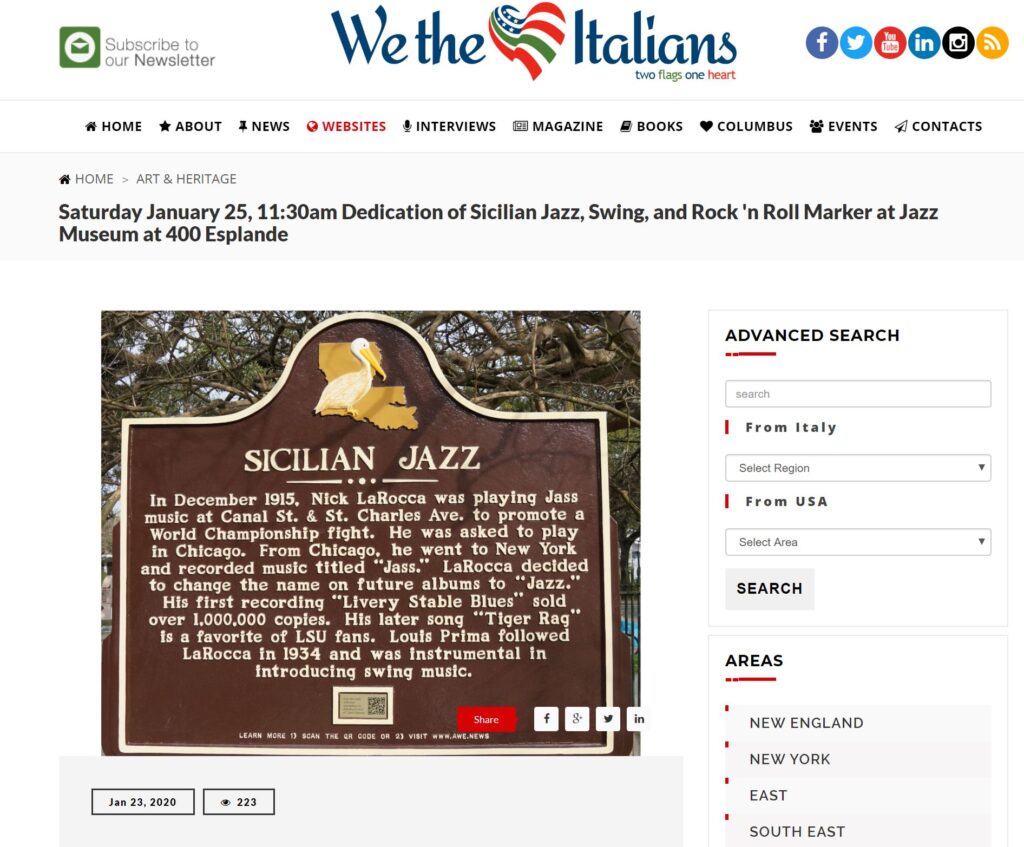

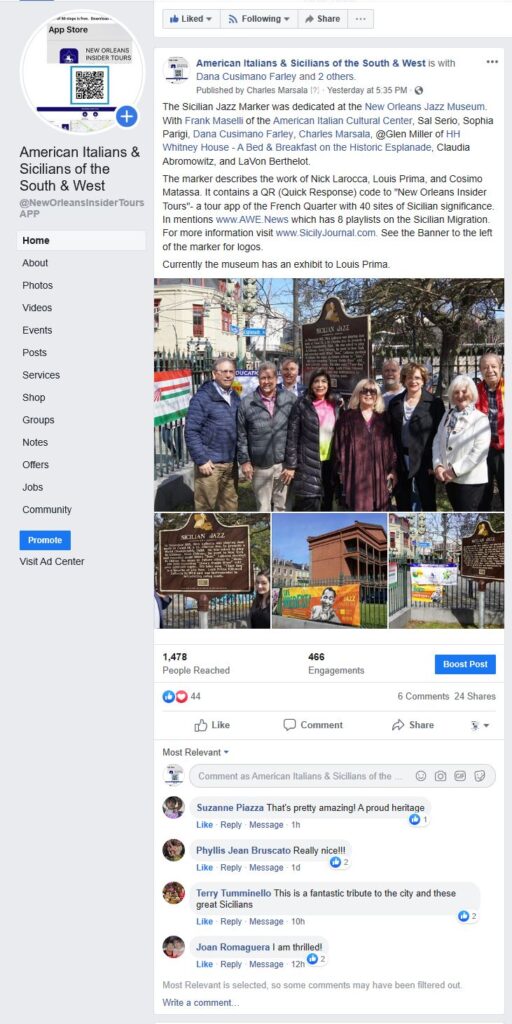

September 2019, after approval by the state, Charles Marsala asked the Jazz Museum for approval on the Sicilian Jazz Marker. The Museum, which is managed by the state, granted approval and erected the marker.

September 2019, Marsala asked the New Orleans City Council and New Orleans Parks and Parkways for approval on a marker regarding the eleven pasta factories that opened in the French Quarter after the Dingley Tariff of 1897 and on the efforts of the Italian Brigade to act as First Responders and police for a peaceful transition in April 1862 of New Orleans back to the Union. During the last week of April 1862, Algiers was burned and looted. New Orleans was policed and protected. The marker also mentions the role of Sicilians in the naming of the “Fighting Tigers” as the LSU Mascot.

In September 2019, Marsala requested the item be put on the Council’s Quality of Life Committee and was denied. He then opted to speak during public comments to items not on the agenda. Here is the link to his presentation and the response by Council Member Kristen Palmer.

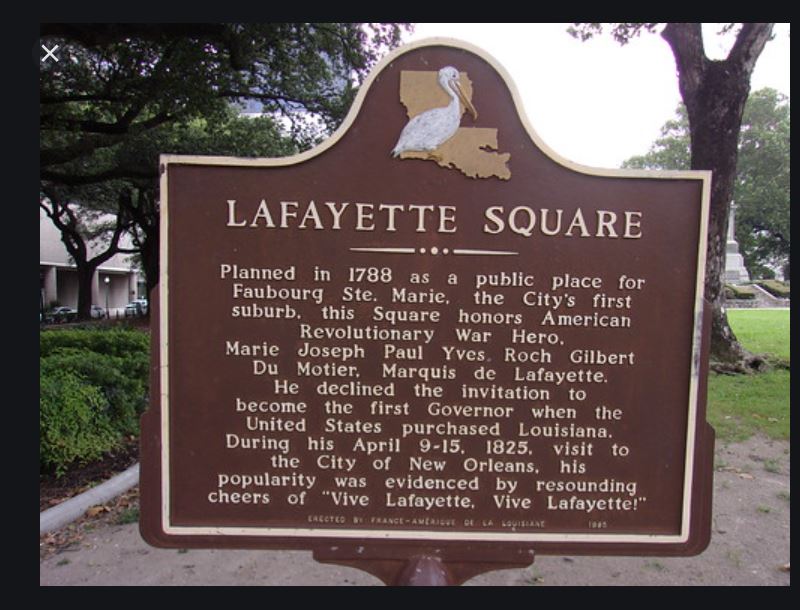

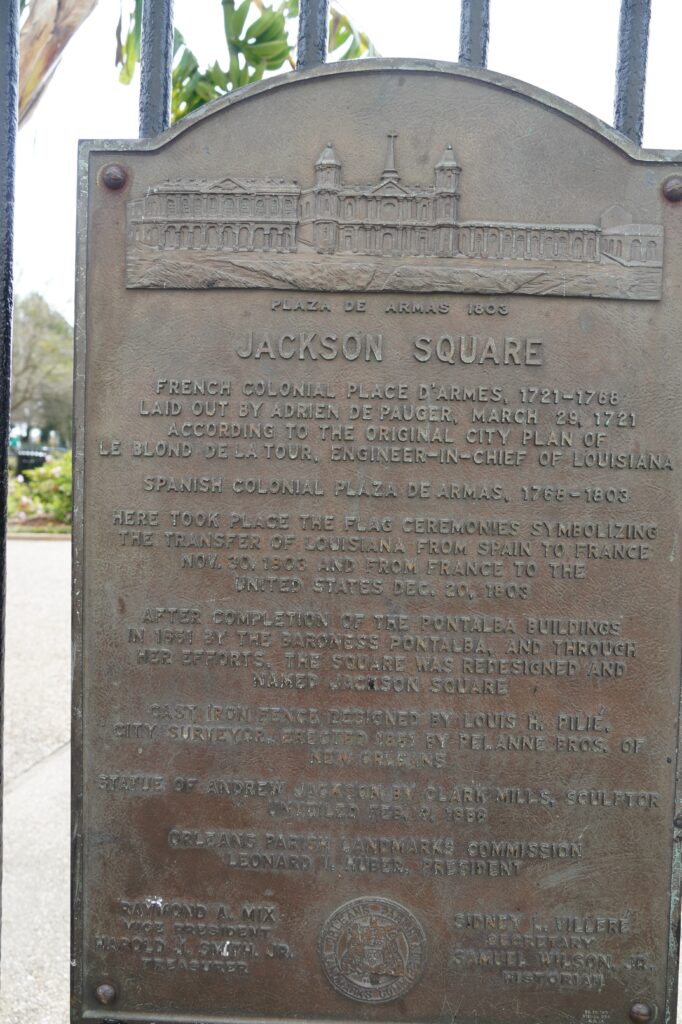

Marsala, who is President of the American-Italian Federation of the Southeast, suggested three locations for the marker: 1. In Jackson Square near the former site of the Taromina Pasta Factory. 2. On Decatur Street near other Historic Markers. & 3. Near the Marker to the Transatlantic slave Trade.

Council Member Palmer stated she was on the Committee the erect six markers to the Transatlantic Slave Trade in 2018 for the New Orleans Tri-Centennial in the French Quarter. No markers to the Sicilian contribution were included or erected by that committee.

City Council Member Kristin Palmer, who represents the French Quarter, suggested during the Quality of Life Committee meeting that a commission of several organizations be formed to study historic markers before the Sicilian Markers could be erected even though for years she has been working on the committee that was erecting the Transatlantic Slave Trade Markers without oversight.

Palmer stated her office would organize the committee. Following the meeting, she emailed that she spoke in error and the Council has no jurisdiction over markers. Her staff also apologized for not responding for three weeks to Marsala’s email, until the hour after he spoke at the council meeting.

New Orleans Parks & Parkways later responded that Jackson Square is not designed to honor military, even though there is a statue to Major General Andrew Jackson and annual ceremonies in honor of all those that fought in the battle of New Orleans. Neither the council member Palmer nor the Director of New Orleans Parks & Parkways would meet with Marsala to resolve the issue.

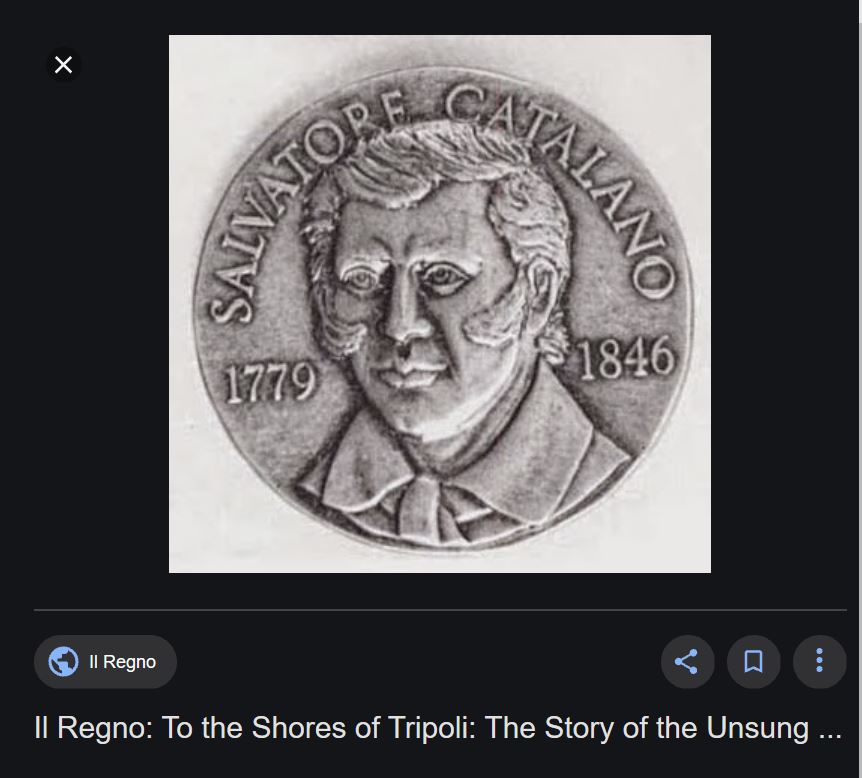

Plans are to donor additional markers for Salvatore Catalano, who piloted Stephen Decatur’s ship and for Mother Cabrini, who has a park named for her. Mother Cabrini arrived in New Orleans in 1892 to open a orphanage for victims of the Yellow Fever pandemics.

In late 2019, Mayor Cantrell announced she wanted to allocate approximately $3 million per year to non-profits that promote the Culture of New Orleans as that benefits New Orleans tourism.

In March 2020, Marsala spoke at the Government Affairs Committee meeting as it reviewed the spending of the $3 million per year to promote Cultural Tourism in New Orleans. He asked for a seat at the table of the Cultural Tourism Commission for Italians /Sicilians.

The Sicilian quest to obtain city approval to recognize the contributions of Sicilians to the safety, culture, and economic development of New Orlerans is to erect 4-8 markers in the area of the French Quarter that was once known as “Little Palermo” or “The Spaghetti District.”

The State of Louisiana has a posted, efficient, and formal process to review and approve markers. An applicant has to provide validation of all text in the marker. The next needed step is a equal, fair, and clear process at the City of New Orleans.

The Story of the Taormina Pasta Factory becoming Progressive Foods

Below is an excerpt from “That’s Amore: Italian Food in America,” the first chapter of The World on a Plate.

The burgeoning Italian community [in late 19th century New Orleans] clamored for tomato paste, anchovies, cheeses, and other products that only their homeland could supply. Sicilian importers like Giuseppe Uddo, the founder of Progresso Foods, responded to this craving. The eldest of six children, Giuseppe grew up in Salemi, a small Sicilian village twenty-five miles from the Mediterranean. After the third grade, he quit school to help support his family. The nine-year-old drove a horse-drawn cart selling olives and cheeses in Salemi and nearby towns. Giuseppe was a venditor, a traditional Sicilian vocation.

On one of his trips, the peddler met Giuseppe Taormina, a successful food merchant, who had many relatives in New Orleans. Taormina took to the young salesman and introduced him to his daughter, Eleanora. The two married and decided to try their luck in New Orleans. Giuseppe and Eleanora, both then twenty-four, sailed from Palermo and landed at the Canal Street docks in 1907.

Since the food trade was “all he knew,” his son Frank said, Giuseppe went to work for his brother-in-law, Francesco Taormina, who had an import business. He lost the job when Francesco closed down to return to Italy to fight in the army. Eleanora’s cousins, also food merchants, hired Giuseppe to work in their warehouse.

The Uddos lived in a crowded tenement in the French Quarter, which was dubbed Piccola Palermo (Little Palermo). They shared a toilet with the other dwellers. Laundry hung in the outside courtyard.

Giuseppe was stranded on Christmas Eve of 1909 when his employers went bankrupt. He now had two young children to support and wondered what he would tell his wife. On his way home through the French Quarter, he met a Mr. Cusimano, who owned a macaroni factory in the district. Cusimano asked the disconsolate Sicilian what was worrying him. After hearing Uddo’s tale of woe, he offered him goods to start his own business and promised him credit to buy more.

Giuseppe was ready to strike out on his own. He had a supply of olives, cheeses, and tomato paste but no way of transporting them to sell. He went back to Eleanora’s cousins and implored them: “If you’re going to go bankrupt, give me your horse.” They agreed and Giuseppe borrowed the money to buy Sal. A godsend, “the horse knew where to go,” Frank said. Since his father adamantly refused to learn English, he depended on the horse to take him on the sales routes to Italian customers. According to Frank, this was the beginning of Progresso: “The horse started the business.”

Giuseppe left home about 3 A.M. to travel to Kenner, Harahan, and other Italian truck-farming communities outside New Orleans. “The roads were terrible and the mosquitoes were so big, you could put saddles on them,” his son, Salvadore, told the New Orleans Times-Picayune. After three days on the road, the peddler returned home and prepared his wares for another trip. He and his wife spiffed up and relabeled the cans of tomatoes they had gotten from Cusimano.

As business grew, Uddo expanded his venture. He replaced Sal and bought trucks. He purchased a small warehouse in the French Quarter on Decatur Street, installing his family upstairs to live and running his peddling operation below. He also opened a grocery on the ground floor and placed his brother, Gaetano, recently arrived from Sicily, in charge.

Just before World War I, his father, Frank remembered, decided to “gamble everything.” Giuseppe took out a loan and bought three thousand cases of tomato paste. When an embargo closed Italian ports, Uddo’s sales boomed, and he used his profits to bring the rest of his family to New Orleans. His parents, Salvadore and Rose, and his sisters, Tomasa and Francesca, joined him. The patriarch made all his family members stockholders. Giuseppe “did not believe in paying salaries,” Frank said.

After the war, Uddo bought a factory in Riverdale, California, owned by the Vaccaros, the New Orleans fruit magnates, which manufactured tomato paste. He sent his brother Gaetano out to run it. The plant was the first in the United States to make the product, which had previously been available only from Italy. The war had taught Uddo that it was too dangerous for his company to rely exclusively on imports.

Giuseppe was always dreaming up new enterprises. He started New Orleans’s first movie theater, built a cigar-rolling factory, and opened a ship chandler’s business in Galveston, Mississippi. But he was “never a good follow-up man,” Frank discovered. Once he began making candles in the back of his warehouse, but they all melted in the city’s torrid heat.

The California cannery was turning out more tomato products than the company could sell in Louisiana. Uddo wanted to tap new markets, especially in the rapidly growing Italian enclaves in the Northeast. “There are more people in New York than there are in Rome,” he told Frank.

Giuseppe joined forces with the Taorminas, the members of another Sicilian trading clan, who had begun a struggling import business in New York City. Frank G. and Vincent Taormina, distant cousins of Eleanora Uddo, and their cousins, Frank R. and Eugene, were floundering when Giuseppe rescued them. Giuseppe advanced the Taormina “boys,” as he liked to call them, vital capital and brought his family to New York in 1930 to help out the firm. Three years later, Frank G. Taormina married Giuseppe’s daughter, Rose Marie. As Frank Uddo tells it, this alliance “cemented things” in the Uddo-Taormina company, the newly merged enterprise.

Francesco Taormina, Eleanora’s brother, sent olives, pomidori pelati (peeled Italian plum tomatoes), and other staples from Sicily to their Brooklyn headquarters. The California cannery sent carloads of tomato paste to New York for distribution. Olive oil was shipped from Tunisia, where Giuseppe’s cousin owned a factory.

Sicilian imports poured into Brooklyn. The business sold sardines, anchovies, and incanestrato, a cheese molded in a wicker basket (canestro), to ethnic groceries. It roasted peppers and marketed salted chickpeas (ceci), which Italians snacked on during feast days and other celebrations. Caponata was a signature item. The Sicilian appetizer, a traditional summer dish, combined eggplant, tomatoes, onions, and celery in a sweet-and-sour blend made piquant with capers, olives, and anchovies.

The company prospered. It developed a clientele among both retailers and wholesalers. The major Italian middlemen who worked the Northeastern market bought large orders of Uddo-Taormina tomatoes. “We were playing both ends of the stick,” Frank Uddo, who was now working with the company, said.

World War II boosted sales. “During the war you could pack anything and sell it,” Frank said. The company had to increase domestic production because “they couldn’t import any product,” John Taormina, Vincent’s son, recalled. In 1942 they bought an old factory in Vineland, New Jersey.