From the book “Creole Italian” by Justin A. Nystrom

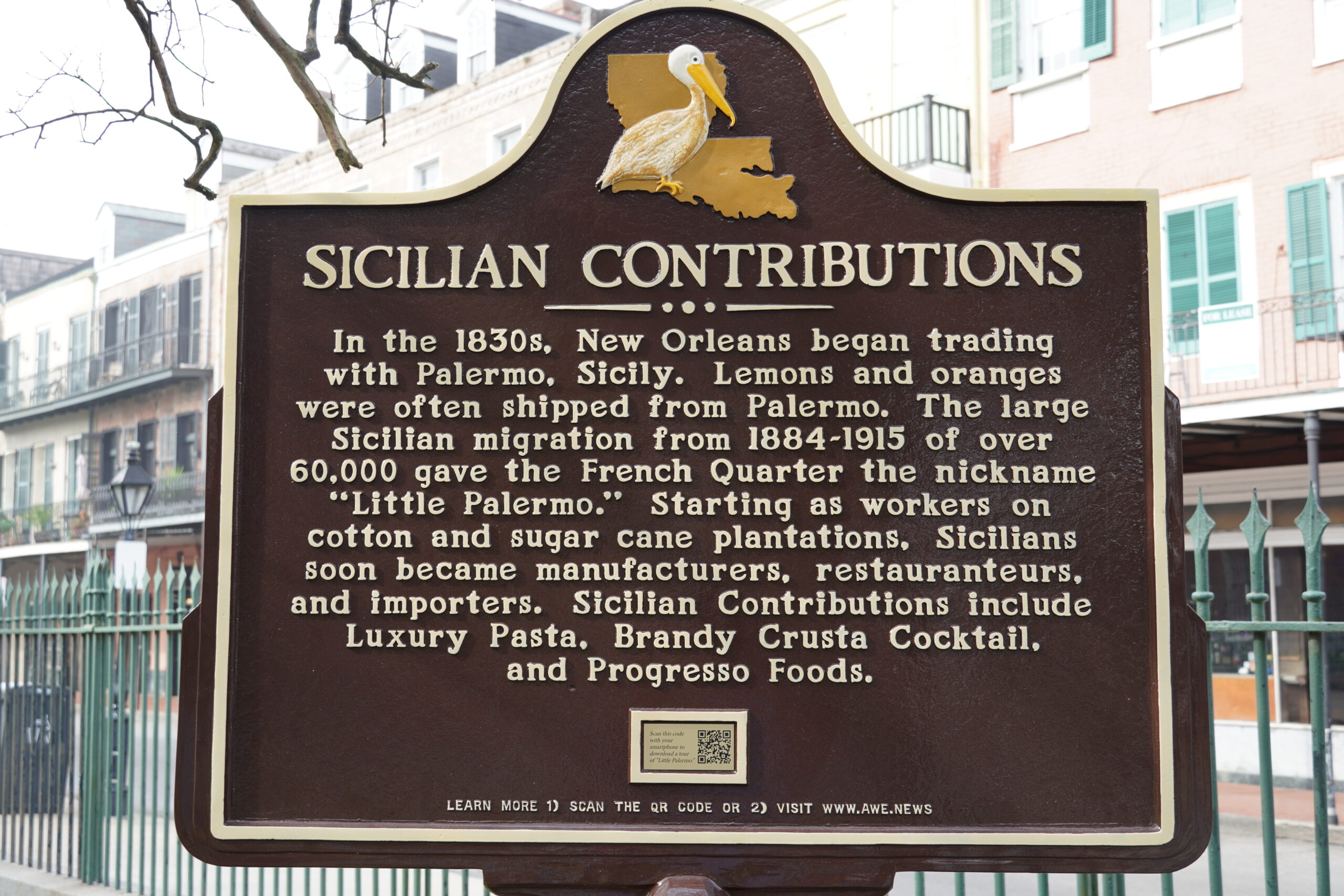

“From both a cultural, geographical, and genealogical standpoint, when we speak of “Italian” in New Orleans we really mean “Sicilian;” the origin of over 90 percent of the city’s self-identifying Italians. Sicilians first came in significant numbers to New Orleans in the 1830s on the back of the Mediterranean citrus trade. Until they were overtaken by California in 1938, Sicily was the world’s leading producer of lemons, a fruit grown in the fertile valleys of the island’s Conca d’Oro. Sicilian citrus merchants established trading houses along Decatur Street by the 1850s, and in decades came to dominate the importation and wholesaling of produce in the Mississippi Valley. Yet this was only the beginning of their ascent: the advent of the tramp steamer around 1880 forever revolutionized their business, cutting the cost and time it took to sail between the Gulf and Mediterranean in half and allowing for diversification in the far more lucrative tropical fruit trade. This steam-powered citrus fleet also offered Sicily’s rural poor relatively cheap transportation to the Americas.

Driven from the island by poverty and political instability and attracted by the prospect of property ownership after a purgatorial tenure harvesting cane, digging levees, and felling pine trees, they came ashore at the Nicholls Street Wharf and melted into the Lower Quarter by the thousands. The eventual arrival of 45,000 Sicilians to Louisiana by 1910 created an especially large and lucrative native market for Italian-style pasta.

The 1897 Dingley Tariff Act

The 1897 Dingley Tariff Act doubled the cost of imported pasta and increased the market for the domestic manufacture of the low-margin product. By 1901, eight significant macaroni factories operated in New Orleans, all but two owned by Italians and only one located outside the French Quarter.

These were in addition to an indeterminate number of cottage pasta makers producing macaroni in a back room of their residence. The question of the local market’s size was addressed through humorous calculation by the Picayune’s Branan. In reply to the Italian consul’s inability to compute the number of his countrymen in New Orleans, Branan joked that one could measure it by the sheer volume of macaroni consumption in New Orleans.

While Branan may have been off in his particulars, there could be no mistaking that the skyrocketing rate of growth in the city’s pasta production spoke to its burgeoning Italian population and an awakening taste for noodles among other Americans.”

The career of Giacomo “Jacob” Cusimano paralleled the rise of the pasta industry in New Orleans. A citrus trader from Palermo, Cusimano arrived in 1882 and by the late 1890s had diversified into macaroni with a small factory at 625 St. Philip. (The site of Ruffino’s Restaurant and Bakery for much of the twentieth century.) His business flourished so much that by 1902 he built a large purpose-built factory at the corner of Barracks and Chartres capable of producing 10,000 pounds of pasta a day.

Today this structure houses Le Richelieu Hotel, but it is hardly the only tangible remnant of Cusimano’s factory. His plant manager, Leon Tujague, formed a partnership with two other non-Italians in 1914 to form the Southern Macaroni Company, whose Luxury Brand pasta is still sold in grocery stores today (though owned by corporate giant ConAgra Foods).

Cusimano’s generosity fostered multiple food industry titans. As the legend goes, in 1908, the merchant lent a financial lifeline to a penniless Guiseppe Uddo, the founder of what would later become Progresso Foods.”