Henri d’ Tonti efforts in 1686 led to the settlement by Bienville of New Orleans. Later in the 1820s, an Italian Consulate was opened. The Mandarin Orange was introduced by Sicilians to America via New Orleans.

On March 17, 1866, the Louisiana Bureau of Immigration was formed and planters began to look to Sicily as a possible solution to their labor needs. Steamship companies advertisements were very effective in recruiting potential workers. . Three steamships per month were running between New Orleans and Sicily by September 1881 at a cost of only forty dollars per person.

Little Palermo” was established by recent immigrants in the lower French Quarter. So many Italians settled here that some suggested the area should be renamed as “The Sicilian Quarter” in the early 20th century. As time passed and they became established, many Italian-Americans moved out of New Orleans and to the suburbs.[4]

Economy

Historically many corner stores in New Orleans were owned by Italians. Progresso Foods originated as a New Orleans Italian-American business.[4] The business established by the Vaccaro brothers later became Standard Fruit.[5]

After they first arrived, Italian immigrants generally took low-wage laboring jobs, which they could accomplish without being able to speak English.[5] They worked on docks, in macaroni factories, and in nearby sugar plantations. Some went to the French Market to sell fruit.[4] Italian workers became a significant presence in the French Market.[5]

Organizations

In 1843 the Società Italiana di Mutua Beneficenza was established. The San Bartolomeo Society, established by immigrants from Ustica, was established in 1879. As of 2004 it is the oldest Italian-American society in New Orleans. Joseph Maselli, an ethnic Italian from New Orleans, founded the first pan-U.S. Italian-American federation of organizations.

The American Italian Cultural Center honors and celebrates the area’s Italian-American heritage and culture. The AICC houses the American Italian Museum, with exhibits about the history and contributions of Italian-Americans to the region. The Piazza d’Italia is a local monument dedicated to the Italian-American community of New Orleans.

Recreation

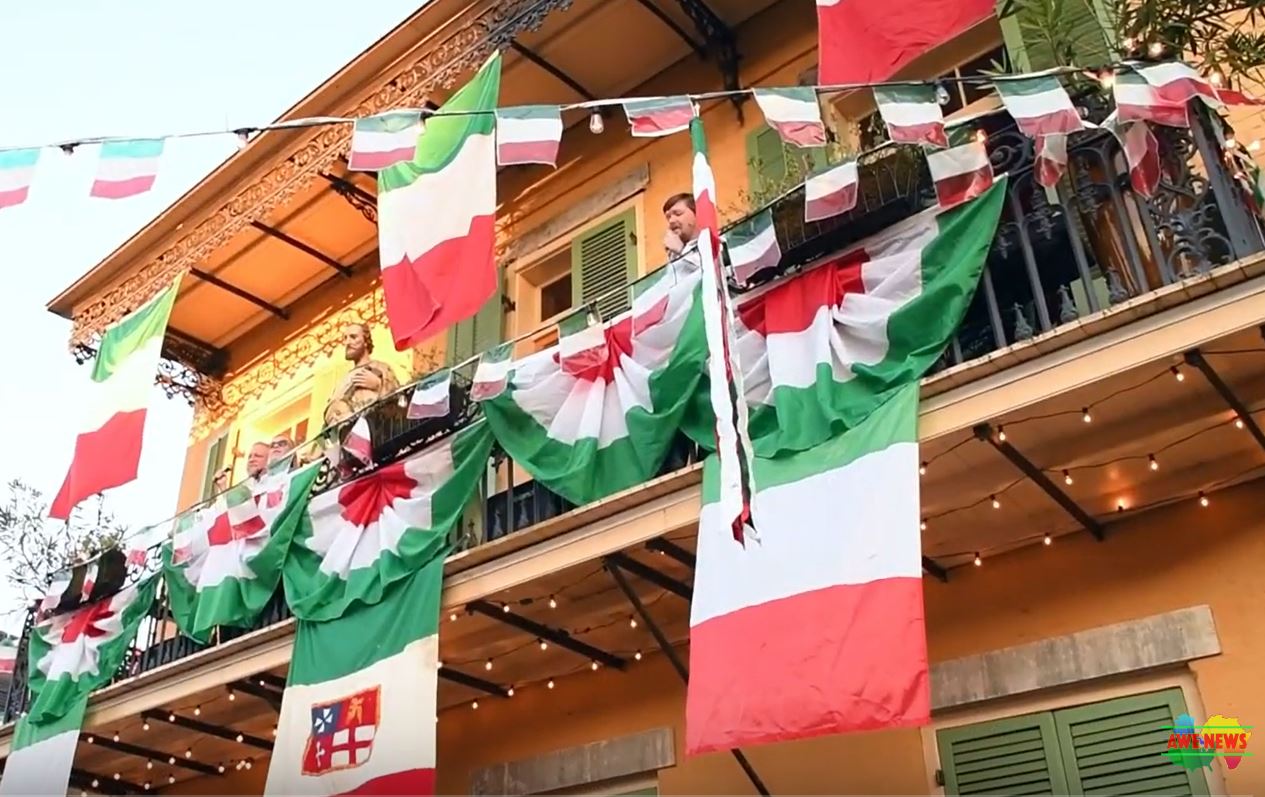

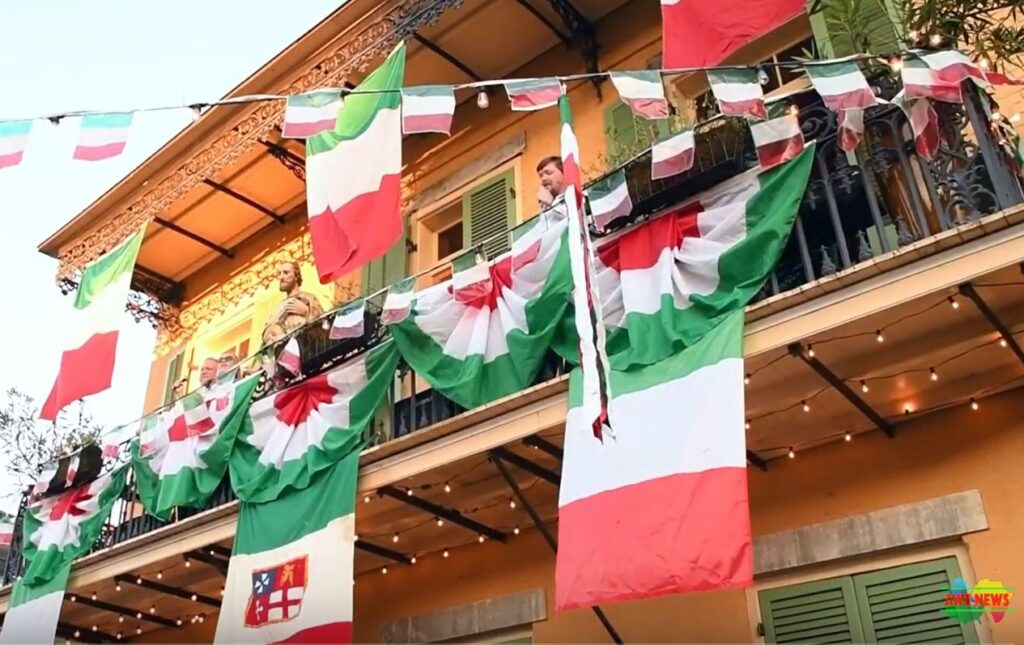

On St. Joseph’s Day, ethnic Sicilians in the New Orleans area establish altars.[4] On that day marches organized by the Italian-American Marching Club occur. The club, which welcomes anyone of Italian origins, started in 1971 and as of 2004 has more than 1,500 members.

Italian Americans originally established the Krewe of Virgilians because they were unable to join other Krewes in the Mardi Gras. In 1936 the krewes crowned their first queen, Marguerite Piazza, who worked in the New Orleans Metropolitan Opera.

Cuisine

Italians in New Orleans brought with them many dishes from Sicilian cuisine and broader Italian cuisines, which influenced the Cuisine of New Orleans. Many food businesses and restaurants were started by Italians in New Orleans. Progresso, now a large Italian food brand, was started by Sicilian immigrants to New Orleans. Angelo Brocato’s an Italian Ice Cream parlor and bakery, established in 1905 by a Sicilian immigrant, is still in existence today. Central Grocery, also founded by a Sicilian immigrant and still in business, originated the muffaletta sandwich, served on the traditional Sicilian muffaletta bread.